- Michaela Neild

- Apr 20, 2020

- 9 min read

When I first entered the STEAM factory for a four-day residency with Teatro Travieso (or Troublemaker Theatre, a theatre collective dedicated to social justice), I experienced a surge of emotions—excitement to be surrounded by others interested in the merging of art and activism; fear of a room filled with unfamiliar faces; and a deep curiosity for the new skills I would learn and the connections I would make over the next few days. I was brought to the residency with a group of students as preparation for an upcoming semester of engaging with and facilitating theater workshops for Columbus’ Hilltop neighborhood with Be The Street (BTS), a community-engaged performance project at The Ohio State University. As a future co-facilitator, it was important for me to understand what my community groups would soon experience. In the following days we got to know each other through icebreakers, played devising theater games, accumulated material we might use in the future, shared mini performances, and discussed the ethics of community-engaged work. We were encouraged to work with the concept of “challenge by choice,” challenging ourselves while participating at our own comfort level. Although I appreciate the autonomy that “challenge by choice” provides I remember feeling nervous about my ability, or lack of ability, to push myself through discomfort. This exact circumstance is a clear example of the need for establishing Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens’ brave space as opposed to safe space.

“As we explored these thorny questions, it became increasingly clear to us that our approach to initiating social justice dialogues should not be to convince participants that we can remove risk from the equation, for this is simply impossible. Rather, we propose revising our language, shifting away from the concept of safety and emphasizing the importance of bravery instead, to help students better understand—and rise to—the challenges of genuine dialogue on diversity and social justice issues” (Arao and Clemens 2013, 136).

As I ventured through the games, discussions, and exercises I was in a constant battle with myself. On the one hand, merely showing up to a devising theatre workshop was already a big step outside my comfort zone. On the other, I knew I was still holding back—that I could have taken more risks. If I was not able to encourage myself to sit with discomfort, how was I supposed to set an example or provide the space for my future community members to do so? This war with my fear of judgement started at a very young age, and it is not a war that is easily won within the duration of a semester or even the duration of a master’s degree. However, I was and still am dedicated to learning how to be vulnerable with the hope that I can spread some courage to those I work with. At the conclusion of our first day with Teatro Travieso, director Jimmy Noriega cautioned us all to “be aware of the dangers of safety, comfort, and group-think.” Reflecting back on my experiences both as a participant in the residency and as a facilitator with BTS, this warning holds true.

In the following weeks my classmates and I drafted facilitation plans and practiced teaching exercises with each other in anticipation of entering our community groups. I was assigned to work with senior citizens at a local senior medical center in Columbus. Having worked with seniors with Parkinson’s Disease in the past, I was excited for the opportunity to engage with and learn from members of a different generation. As my co-facilitator and I thought-up ideas for our workshops, I kept the words of a mentor in the back of my mind: “be prepared for nothing and ready for anything.” I wanted to create a facilitation plan that was detailed enough to support us if we had extra time, but loose enough to provide room for adapting to the people and the environment. I used my experience as a certified Pilates instructor to find creative exercises appropriate for different ranges of mobility, endurance, coordination, and memory. My co-facilitator was very good at considering how we would craft language and space that was inclusive and supportive, and I was good at structuring materials and organizing people. Together, our strengths fostered an ability for us to be both leaders and listeners within our community.

Prior to my involvement with BTS, I had taught dance classes within many different community settings. I went into the community-engaged performance field believing that my job was to take the access to artistic expression that I had and to share it with those for whom access and/or resources were limited. I know, now, that community-engaged work is, as applied theater professor Jan Cohen-Cruz states, a practice of “call and response.” In her book Engaging Performance: Theatre as Call and Response, she talks about the importance of reciprocity, of both parties—in this case facilitators and community members—benefiting from the project. As I entered the senior medical center for the first time, I felt anxious. My journal entry from that day read “I was the first person to arrive today, and I entered the space in a funk. I was feeling tired, unfocused, overstretched, and anxious. I tried to keep my internal dialogue from influencing the vibe of the room as people arrived. I think entering collaborations and community spaces like this is the toughest part of the experience. How I enter on the first day sets a tone for how people will perceive me as the sessions continue.” This first-day reaction parallels with a piece of advice Jimmy Noriega gave us on our first day of the residency. His advice was for us to be okay with feeling overwhelmed and to make our roles as facilitators known in the beginning. As we progressed through exercises that day, it comforted me to see that same nervous energy in the community members. Eventually as a group, our shared anxiety became shared excitement. We closed our first day by taking stock of the exercises our community collaborators enjoyed and by offering suggestions for future workshops.

“Translated to engaged performance, call and response foregrounds the many opportunities for inter- activity between a theatre artist and the people involved in the situation in question. These exchanges happen at various points along the performance process: the early phases, especially research and devising, or perhaps a workshop not intended to lead to anything else; the duration of the play itself; and the period following, whether a talkback conversation, story circles, or more long-term actions that the production supports or inspires. The process is iterative: the call may be initiated from a community, and the response may come from an artist, who then sets forth a new call directed to an audience. The overall process of such art must be reciprocal and must benefit the people whose lives inform the project, not just promote the artist…An active relationship between actors and community, not only the connection among the actors, is at the heart of the work”(Cohen-Cruz 2010, 1-2).

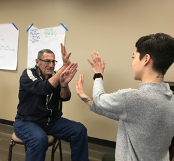

During our second workshop I began to get a glimpse of the personalities in the room. I took a mental inventory of those who seemed outgoing and those who seemed to be more introverted. My journal reads “I noticed that she, too, shows some signs of insecurity. During Bam-Pow she seemed anxious about sharing. When we did Ball Toss she said she ‘was just happy we hadn’t asked her to tell a story.’ During Machine, she seemed very nervous and said that she ‘just didn’t know what to do.’ Once I prompted her to think of making sound with her body instead of her voice she began to clap. A minute later, in the same shape, I looked back and saw her clapping, in her pose, smiling and laughing with the group. Seeing her make it through her discomfort and into enjoyment felt like a win. I hope to continue finding gentle ways to pull her out of her shell.” I thought back on my experience with insecurity during the Teatro Travieso residency and decided that in order to support this individual, I would have to step up. I would have to lead by working through my own discomfort in an effort to create a “brave space” so she could do the same. Two weeks later, I wrote “These last two weeks have brought me a lot of joy. It seems like we’ve reached a point where our group trusts us, or at least is becoming more comfortable with working through discomfort. Not only did I notice this in the group, but also within myself. It’s wonderful to be both giving and taking from each other and I appreciate the support they’ve shown us as facilitators, which has made me feel more confident in my leadership skills. I hope they are feeling a response parallel to the one I am discovering in this work.” As weeks passed our sense of community began to grow. We learned about each other’s likes and dislikes, families, careers, and memories. Most of our time was spent sharing stories through words, sounds, and movement. We created more material than we knew what to do with, but eventually we started to feel the pressure of time. “Creative groups need to nurture an atmosphere where people feel safe enough to take risks; otherwise, only heroes will bring forth creative ideas; others will censor themselves (Kerrigan 2001, 86).

My co-facilitator and I were repeatedly forced to make in-the-moment decisions, cutting exercises from our plans and then choosing which remaining exercises were most important for the group. Outside of our workshops I struggled with having adequate time to reflect on what had been accomplished the previous week in order to build a plan for the next. All along, I believed that we had taken Jimmy Noriega’s advice to begin with small moments and gradually build them into a cohesive whole, but as our performance date approached it became clear that we weren’t bringing our small moments together quickly enough. One of my last journal entries before the Covid-19 pandemic halted our work with the senior center read “I’m realizing that our facilitation plans are really focusing on the particular day but are not thinking ahead to the big picture of what we are trying to do. I believe we are doing a good job of scaffolding in each facilitation plan individually, but we still don’t know what it is we are building up to overall. It’s difficult to reflect adequately enough to know where we are building to. It feels like our time between reflection and building the next plan is so short, and I’m constantly struggling for more time to consider where to go next.” This was a major turning point where I began to recognize the importance of reflection.

Looking back on our last few weeks at the senior medical center, I can’t help but find irony in our relationship with time. It was only a month ago that we were scrambling, gripping onto as much time as we could to prepare. Now, most of us have more time and less to do. The university’s shift to a digital platform has been an adjustment for all but has been particularly problematic for continuing outreach with our senior community. With some participants having limited or no access to technology, staying in touch has been difficult. My co-facilitator and I brainstormed the possibilities for our group to create something tangible. We called community members one by one to check in, offering ways of making something new together. My conversations with participants gradually turned into discussions on how they were passing the time, what was bringing them joy, and the good deeds we were seeing in our neighborhoods. Some opened up about the hardships they were experiencing and others shared photographs of their pets. Although it doesn’t feel like closure, it does feel like we succeeded in creating a brave space for our community to share their stories. One participant told me how she believes that in times of crisis, we find our true selves. She said that now is an opportunity to start new, to decide who we’d like to be when the pandemic is over.

As I move forward with my academic and professional careers, I want to continue chasing discomfort and taking risks. I will continue using applied theatre techniques and community-engagement as a platform for people to share their stories. There are multiple divisions between people—geographic, cultural, societal, and political barriers, but covid-19 has and will continue to affect us all. I believe that when the covid-19 crisis ends, there will be a need for creative expression, building connections, and sharing stories through art like never before. In my research I am questioning if/how academia prepares students for community-engaged collaboration with vulnerable populations. As a graduate student and an artist who has been working with underserved communities for the last few years, I still don’t feel adequately prepared for this work. I question how educators can begin this training at an earlier stage of a young dancer’s academic career. I am excited to bring the skills I’ve learned into my service with both local and international underserved communities as I forge ahead with establishing OSU’s Movement Exchange chapter. Movement Exchange unites dance and service through its network of university chapters, international dance exchanges, and year-round programs in local, underserved communities. For many of our chapter body members, this will be their first time working in/with/for vulnerable populations. I hope to build from the work of Jan Cohen-Cruz, Jimmy Noriega, Brian Arao, Kristi Clemens, and Sheila Kerrigan to provide applied-theatre workshops, facilitation strategies, and discussions around the ethics of entering and exiting at-risk communities for our body members in order to prepare them for our exchanges abroad and for our work locally. I hope to build a brave space within our chapter’s community, offering a space where students feel supported to take risks as they learn about cultures different than their own, through movement.

Works Cited

Arao, Brian and Kristi Clemens. 2013. “From Safe Places to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice” in The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators, edited by Lisa M. Landreman. Sterling: Stylus LLC.

Cohen-Cruz, Jan. 2010. Engaging Performance: Theatre as Call and Response. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kerrigan, Sheila. 2001. The Performers Guide to the Collaborative Process. Portsmouth: Heinemann.